How did China Become the World’s Second Economic Power?

China has become the world’s second economic power in four decades, to the astonishment of many observers and thanks mainly to four factors. The first is Deng Xiaoping’s opening-up-to-the-world policies and the 1979 Equity Joint Venture Law. Together they have allowed (among other things) foreign capital and Western companies to enter China, transforming the domestic economic landscape entirely from one that is traditional and obsolete to one that is dynamic and modern. The second factor is the State Strategy outlined in the various Five-Year Plans (FYP). This strategy has led to the gradual flourishing of the Chinese economy and that of some industries targeted by the State in the FYP. The third factor is China’s most precious treasure, namely its labor force, whether the cheapest or the most educated. Estimated at over 786 million in 2017, this labor force has allowed China to become the world’s factory in only three decades. And finally, the fourth factor is China’s diaspora or overseas Chinese (Huáqiáo who are Chinese citizens residing abroad and Huáyì who are of Chinese descent living abroad, regardless of their citizenship). On the one hand, the Chinese diaspora has sent remittances estimated at $64 billion in 2017, as reported by the World Bank’s Migration and Development Brief. On the other hand, some of these overseas Chinese came back home to benefit from China’s booming economy and offer their expertise gained abroad, mostly in Western countries such as the U.S.

That said and in addition to these factors considered as catalysts to China’s booming economy, China used several internationalization strategies to shake its economy from the impoverished state left by Mao Zedong. What are these strategies? What is China’s and its instruments’ (namely its companies’) modus operandi? How did China become the second economic power in the world?

The answers to these questions can be summarized in several factors. Let’s start with the first one.

Trade: The yin of China’s internationalization strategies

The most striking facet of China’s internationalization strategies is without doubt trade. The number of China’s largest companies in the world has been growing steadily since 2000, prompting Fortune 500 to talk about the “Chinese Factor” in 2006 (China was then the only country that was able to bring in four new companies into the ranking that year). The number of dragons continues to grow. From 2000 to 2018, their number has been multiplied by ten (going from a mere 12 to 120). Meanwhile, the first of the ranking, the U.S., continues to lose places by more than a third (going from 197 to 126 – – only six companies more than China, predicting that the Middle Kingdom will dominate the ranking in 2019), while the second of the ranking, Japan does the same by losing half of the places (going from 103 to 52).

China has also started in an insidious Sun-Tzu style to conquer the world using its little dragons that have invaded mature markets, beginning with thousands of small Chinese businesses in Africa and South America that pave the way to the biggest ones, encouraged by the Go Out Policy launched in 1999.

But first, the West entered China’s market. Indeed, Western companies (regardless of their size) transferred their production in China to enjoy economies of scale and to secure shares of the vast domestic market as well as to export their products to the rest of the world. Chinese companies’ sensu lato then took control of the much more lucrative local market and have started invading the global market. Undeniably, Chinese companies invade their domestic market from the outset with economies of scale, since the Chinese market itself is gigantic, something that a Western company cannot afford to do at home from the beginning. A Chinese company that is emerging nationally is already a strong company having won a victory over its competitors. It has a strong basis from the start in a highly fragmented transitional market with provincial protectionism that makes competition between Chinese companies harder and which pushes them to maintain and cultivate privileged relations with the authorities (Guanxi’s importance here is vital).

A Chinese company’s presence in the local market disturbs international competition and attracts Western companies that propose commercial agreements. Given the massive size of the untapped Chinese market, these companies compete easily (to a certain extent) in the global market and disrupt the established order, as is the case with Haier and Huawei that started sweeping Africa, Asia and that has penetrated Eastern Europe. To do so, they have the help of state logistics, financial aid and tax exemptions, an assistance that is decried as unfair by Western countries and that must be stopped, as stated by the U.S.

That said, the Achilles’ heel of Chinese companies’ candidates to internationalization is and remains branding, something that is still not yet massively developed because of China’s goods reputation of bad/low quality. At the same time, despite the current trade war, China is robust enough to tackle what the U.S. is trying to do with its tariffs since it has developed its New Silk Road (the Belt and Road Initiative) weaving its web by land and sea on three continents, but what helped China’s trade reach these heights?

Joint-Ventures: The growth engine of the Chinese economy locally and abroad

The growth engine of the Chinese economy (especially at the domestic level) is undeniably joint-ventures (JVs). They are the best way for foreign enterprises to do business guaranteed by the Chinese state. With nearly 20,000 foreign companies settling in China yearly since 1978, the total investment volume is now over 100 billion, making China the world’s factory, producing in large quantities at low cost to the point of becoming the center of the planet’s endemic growth.

To maintain their position in the Chinese domestic market or to expand it, JVs are forced to re-invest. The bigger the investments and the foreign company, the more important the Chinese counterpart should be. Nevertheless, larger Chinese companies may, in their thirst to attract foreign capital, accommodate smaller foreign firms as well and this is where lishu becomes a key factor.

Lishu represents the links between state hierarchy and enterprises controlled by central government, provinces, cities and prefectures, rural and urban communities. JVs develop relationship networks to minimize their costs and maximize profits by seeking strategic alliances. What muddies the waters is the rampant corruption that plagues all levels of Chinese society, including the highest. Indeed, the perception index of corruption in China has worsened; China’s rank went from 40 in 1990 to 79 in 2016 according to Transparency International, despite Xi Jinping efforts to eradicate it. It is a plague that will not disappear anytime soon, one that puts sand in JVs’ gears on top of the fact that JVs are becoming more and more criticized by foreign companies since the famous cases of Danone Wahaha and Heartland Spindle that turned sour to the advantage of their Chinese counterparts who enjoy the support of the whole state apparatus.

Actually, Chinese companies continuously evaluate the costs and benefits of their relationship with foreigners. As soon as they find a better partner, they get rid of the current one and go for the new one. Fortunately, China allowed other forms to bud under its ‘paternalist’ control, such as the share-risk partnership and even the private sector at the domestic level, while it allowed new ways to do business at the international level. What are they?

Mergers and Acquisitions: The gate to the global market

The purchase of foreign companies around the world has accelerated in recent years (e.g., China Mobile’s acquisition of Paktel in the telecom sector or Sinopec buying shares in Repsol Brasil for $7.1billion). The most striking examples are the purchase of badly bankrupt or failing businesses in the U.S., such as what happened in the Rust Belt where Chinese interests bought many about-to-close companies, and all machinery and documentation were sent to China.

A new trend that has been observed for some time in commodities is that Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs) are acquiring large companies operating in the mining and energy sectors. However, they are encountering more and more resistance from Western states, as was/is the case in Australia where several purchase attempts failed (e.g., UNOCAL stopped from being purchased by CNOOC). Some countries realized too late what was happening and are trying to react to stop China’s insidious invasion, especially now that the race for commodities is starting to get tougher with India and Brazil’s rise, who also want their share of the market to fuel their growth.

China has also created stock exchanges in which both Chinese and foreign companies are listed. Chinese companies operating on their stock market have access to investments abroad as well as through mergers and acquisitions. And with China being the world’s first forex reserve ($3.2 trillion in reserves held in Q1 2018 according to the IMF), China’s state has had a firm stronghold on capital controls and on the oversight of overseas investments since late 2015. This policy was initiated to maintain financial stability and to more efficiently control the exchange rate after the 2015-2016 yuan devaluation, but what fuels China’s economy?

Local and Foreign Supply Chains Logistics: The fuel of the Chinese economy

Despite China being officially the world’s first buyer of raw material, Chinese state companies divert a large volume of raw materials from official networks, mainly from Africa. Their modus operandi is well known. They settle in developing countries by buying or renting land, extract what they can or grow what they want and then send it directly to China without using the official channels. No need for markets and no paying in foreign currencies. In this, China still takes advantage of its title of leader of the Third World inherited from Mao’s era when barter between countries was encouraged.

The modus operandi of Chinese enterprises in the official channels varies. On the one hand, big Chinese companies settle in developing countries, get contracts to build infrastructure and/or modernize them; moving their whole of labor force from China. They barely interact with local people (instead creating Chinese ghettos) and do not interfere in the political affairs of the country in which they live, as is the case in Angola (e.g.). On the other hand, Chinese small businesses observe the local market, import goods almost identical to those that sell well on the spot and break prices, leaving the local industry to struggle for its survival. This is how the chicken industry in Zambia and the bikini industry in Brazil were severely hit.

In general, China imports wood from brazil; agricultural products from Argentina, East Asia, and South Asia; Venezuela’s minerals and hydrocarbons; and hydrocarbons and raw materials from Central Asia and Africa. It exports agricultural products to Africa and Asia. Recently, China began building assembly plants in Africa (Algeria and Senegal) and Asia. And with the establishment of the Belt and Road Initiative, roads and maritime routes will be dedicated to filling China’s needs regarding raw materials and energy, and it will be a more direct way for China to export its goods. But then again and despite all of this, how China’s economy will maintain its growth and its leading position as the second world economic power aspiring to dethrone the first one that is the U.S.?

Technology, R&D, and Innovation: The keys to global domination

Chinese companies’ innovation at home consists mainly of buying back companies or creating JVs to take advantage of the ability to innovate from abroad. Foreign firms invest in R&D in China because of the abundant, educated and inexpensive workforce. A culture of innovation, R&D, and technology is increasingly taking hold in China following government guidelines, as Wan Gang (Minister of Science and Technology) told the media: “China needs to enter the ranks of innovative countries and become a big technological innovation power by 2050.”

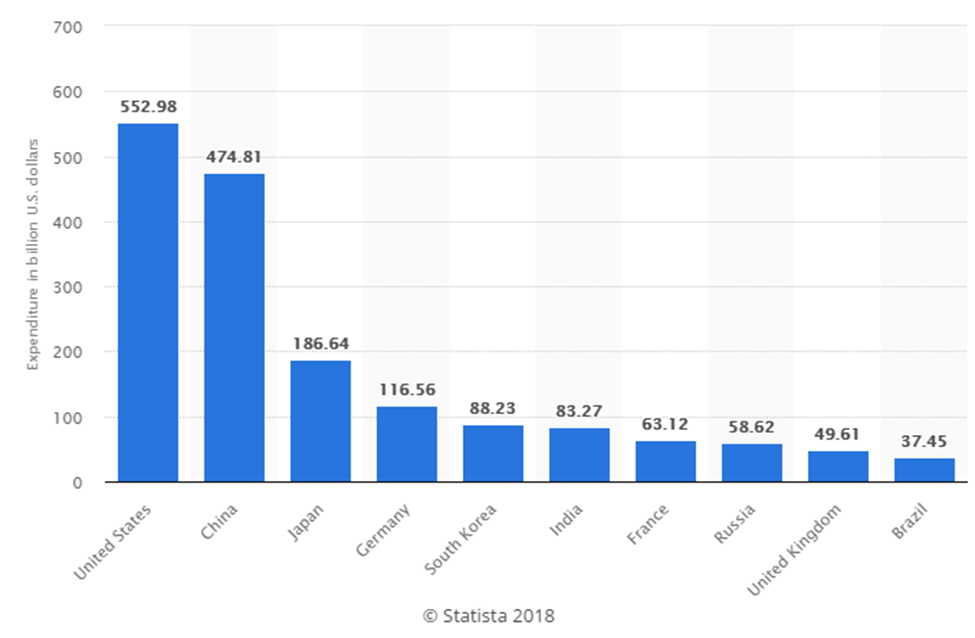

The R&D expenditure of the 100 largest dragons was $ 33.76 billion in 2008, spending more than twice as much (2.3 times) as South Korea, while in 2017, it is estimated to have spent $279 billion in R&D (more than 8 times in 8 years!). Leading other countries by its gross research and development (R&D) expenditure worldwide in 2018 (in billion U.S. dollars) shows that China is nearing the U.S. at a quicker pace.

There is still much to be done for China to overcome the image of a hacker, imitator and thief of Western intellectual property without worrying about patents and licenses to sell them in the Southeast Asian and African markets. To work on this image change, more and more tripartite alliances (government-university-industry) are being established to accelerate the pace.

While the opportunities and challenges that await the Chinese regarding the internationalization of their R&D are still little known, there are opportunities for the emergence of Chinese R&D through the return of Chinese expatriates and of Chinese students sent around the world. Moreover, China’s companies can call upon the 47 million Chinese people of the diaspora. This unique situation has allowed China to be among the world’s top 20 most innovative economies in 2018, while the U.S. has dropped out of the top 5 as highlighted in the 2018 Global Innovation Index report.

The new modern Chinese diaspora is considered to be wealthy and highly educated, unlike the first poor one, the coolies who were cheap labor for many host countries like the U.S. and Canada. The Chinese diaspora continues to weave its web all over the world (thus serving the CCP’s political interests), even in parts of the world that did not interest it in the past, as is the case for Morocco today.

Delegations explicitly sent to receive advanced academic training in technology and international business administration are becoming the norm. In 2003, 20,000 highly skilled personnel trained in technology and business administration returned to China to work. In 2017, Chinese students abroad totaled 608,400 according to the Ministry of Education of the PRC. This figure indicates a multiplication of over 15.6 times in eighteen years (38,989 students in 2000), while in 1978, there were only 860 Chinese students abroad!

These students focus on the following areas: economics, finance, international trade, business administration, telecommunications and high technology. The case of Lattice Power, created in 2006, and crowned by MIT Technology Review in 2011 as one of the 50 most innovative companies, is convincing with its workforce composed of graduates from around the world.

That said, the Chinese went from the duplication phase (blind imitation) to the creative duplication phase (copying with minor changes) by developing their standards, thus preparing for the local innovation phase. These phases are found in all sectors activity targeted by government guidelines. Furthermore, in China’s twelfth FYP (2011-2015), it is specified that China must develop the seven emerging industries, namely biotechnology, new energies, the manufacture of high-end equipment, energy savings and environmental protection, alternative fuel cars, new materials and next-generation information technology. And Chinese companies answered the CCP’s call massively.

Talking about innovation and R&D brings up the subject of intellectual property rights. Historically, intellectual property rights have never been codified. Confucianism and Neo-Confucianism do not recognize the notion of copyright that the Confucian State must uphold. The same goes for contracts between individuals or between companies. The state does not intervene in case of conflict. The neo-Confucian milieu does not favor denunciation within the company, considered to be treason, and so piracy becomes a regular activity in a society where it has never been considered a crime.

What is interesting is that Chinese brands have not yet massively penetrated the Western market and have therefore not been confronted with the practices of imitation and piracy. This subject is still little known and less documented. However, many Chinese companies started filing patents in China and internationally (e.g., Lattice Power has filed more than 150 patents). Even more telling, the Chinese government is ready to enact legislation protecting intellectual property rights to encourage R&D in China. China, cornered by innovation’s norms, has conceded to protect the intellectual property right it has never recognized, but still, to date no concrete action has really been taken by the government.

The Chinese state: The holder of the keys to success

In conclusion, the spearhead of the Chinese economy lies, in fact, in its companies (small and large) that are instruments of another company, namely the Chinese state, as it is the state that holds the resources and their allocation through its FYPs. It is the state that regulates the Justice sector and interprets it for its companies. Judge and party, the PRC distorts the economic game since his hand is visible both inside the country and abroad.

China’s instruments to ensure global domination are in two categories. The first one is JVs that are formed on the same model and follow the same internationalization strategy. When the strategic objectives differ from those set by the PRC, the latter triggers a process of questioning. The second one is SOEs whose strategy is set by the PRC. They do not care about resources, expenses or profitability as they operate in a logic that is far from capitalism.

These Chinese companies have become insidious war organizations, just like the silent force of water undermining the foundations of a structure. These organizations do not take prisoners, but they create armies of unemployed people in the rest of the world, which leads us to raise several questions: Is the rise of protectionism everywhere a reaction to China’s rise or no? Is the current trade war carried out mainly by the U.S. (beyond the way it is being done) have a reason to take place or no? Will China overcome successfully all the hurdles on its path to global domination?

This article is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International licence.